As I

write this update it is now the Winter of 2013, and seven years

have passed since purchasing our first Epiphone upright bass. When

we purchased our 1941 Epiphone B1 that I affectionately named

“Gunner” in September of 2006, we had no idea what brand of bass

it was — the bass spoke to me. I could not get it out of my mind.

The bass was well used and had the correct character marks to

prove it had been a workhorse for a real bass player. We purchased

it not knowing its heritage or the research journey it would lead

us on.

Once we had the bass in hand we needed to make a major neck repair do to a shipping mishap courtesy of Greyhound Bus. When the bass was repaired by my husband Lonnie Hamer and made playable once again, my research and love of Epiphone basses began. Within a short period of time we figured out it was an Epiphone bass, even though it was missing the iconic brass and white enamel tail badge. It had the shadow of the badge and the three tiny pinholes where the badge had been anchored to the tailpiece.

The features I love about the Epiphone upright bass are the massive factory-carved scroll, the medium thickness of the classic two-piece neck (there are exceptions), the stylized F-holes and the enameled tail badge. These are the characteristics of an Epiphone that make identifying them unmistakable in comparison to other American-made plywood basses from the same period, the early 1930s to late 1960s.

Once we unlocked the mystery of what brand of bass we had, I discovered that very little information existed on the history of the Epiphone upright bass. If you own a Kay, American Standard or King plywood bass from the same era, you can easily find two great websites that will give you history and guidance for identifying your bass. The Epiphone proved to be more challenging. I found a little history about Epiphone mandolins, banjos and guitars, with only a few references to the basses, not enough to satisfy my curiosity. So here is where our quest for knowledge about Epiphone basses begins.

The information we have researched and gathered here on our website comes maintly from a great book published in 1995 by Epiphone official historian Walter Carter, and our database documenting individual Epiphone basses. We have owned or played in person over 75 Epiphones and Gibson-Epiphones. Seeking accurate and factual examples of the Epiphone upright bass we have acquired examples of all five prewar models, and can offer pictures and accurate descriptions of the B1, B2, B3, B4 and B5. The database project has grown to a catalog over 280 basses, or 7% of all the manufactured Epiphone and Gibson-Epiphone basses. We have gathered this information that we will openly share, but by no means do I consider this to be an official history. This quest was intended to be only to satisfy my curiosity, but the journey has become so much more.

Once we had the bass in hand we needed to make a major neck repair do to a shipping mishap courtesy of Greyhound Bus. When the bass was repaired by my husband Lonnie Hamer and made playable once again, my research and love of Epiphone basses began. Within a short period of time we figured out it was an Epiphone bass, even though it was missing the iconic brass and white enamel tail badge. It had the shadow of the badge and the three tiny pinholes where the badge had been anchored to the tailpiece.

The features I love about the Epiphone upright bass are the massive factory-carved scroll, the medium thickness of the classic two-piece neck (there are exceptions), the stylized F-holes and the enameled tail badge. These are the characteristics of an Epiphone that make identifying them unmistakable in comparison to other American-made plywood basses from the same period, the early 1930s to late 1960s.

Once we unlocked the mystery of what brand of bass we had, I discovered that very little information existed on the history of the Epiphone upright bass. If you own a Kay, American Standard or King plywood bass from the same era, you can easily find two great websites that will give you history and guidance for identifying your bass. The Epiphone proved to be more challenging. I found a little history about Epiphone mandolins, banjos and guitars, with only a few references to the basses, not enough to satisfy my curiosity. So here is where our quest for knowledge about Epiphone basses begins.

The information we have researched and gathered here on our website comes maintly from a great book published in 1995 by Epiphone official historian Walter Carter, and our database documenting individual Epiphone basses. We have owned or played in person over 75 Epiphones and Gibson-Epiphones. Seeking accurate and factual examples of the Epiphone upright bass we have acquired examples of all five prewar models, and can offer pictures and accurate descriptions of the B1, B2, B3, B4 and B5. The database project has grown to a catalog over 280 basses, or 7% of all the manufactured Epiphone and Gibson-Epiphone basses. We have gathered this information that we will openly share, but by no means do I consider this to be an official history. This quest was intended to be only to satisfy my curiosity, but the journey has become so much more.

HISTORY:

Epaminondas

“Epi” Anastasios Stathopoulo was born in 1893. He inherited the

family business in July 1915 at the tender age of 22, when his

father Anastasios died. In 1917 Epi gave the family business a new

name, House of Stathopoulo, and continued the family tradition of

making mandolins. By 1924 times were changing with the great age

of jazz, and Epi expanded his business by adding banjos. The

business was renamed again in 1928 to Epiphone Banjo Company. The

factory was in the New York City borough of Queens, in the old

Favoran factory in Long Island City.

The market crash of October 1929 changed the direction of the business, and Epi added guitars to the product line. Through the '30s there was a well documented war between Epiphone and Gibson for share of the guitar market. By 1935 the company name had changed again to simply Epiphone Inc., and factory operations moved to Manhattan. Epi also added a showroom where musicians would come to jam and hang out on Saturday afternoons.

In 1939 Gibson introduced a family of violin instruments that included an upright bass, and Epiphone had to respond with one of its own, introducing a line of five models in the January 1941 catalogs. I have found examples of print ads from a 1940 Metronome magazine showing the first new Epiphone bass, before the B1- B5 lineup was established.

The market crash of October 1929 changed the direction of the business, and Epi added guitars to the product line. Through the '30s there was a well documented war between Epiphone and Gibson for share of the guitar market. By 1935 the company name had changed again to simply Epiphone Inc., and factory operations moved to Manhattan. Epi also added a showroom where musicians would come to jam and hang out on Saturday afternoons.

In 1939 Gibson introduced a family of violin instruments that included an upright bass, and Epiphone had to respond with one of its own, introducing a line of five models in the January 1941 catalogs. I have found examples of print ads from a 1940 Metronome magazine showing the first new Epiphone bass, before the B1- B5 lineup was established.

The

46-page 1941 Epiphone catalog introduced the new line of five

basses.

B1

$105.00

B2

$125.00

B3

$150.00

B4

$175.00

B5

$250.00

Epiphone was in a period of great expansion and innovation. The

only force powerful enough to stop its progress was the bombing of

Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Nearly all bass makers dropped

what they were doing to join the war effort. Epiphone suspended

guitar production to make aileron parts for aircraft.

The company emerged from the war with a different face: the man whose name was on every musical instrument had died. Epi passed on June 6, 1943 at the age of 50 from leukemia. This changed the fate of the company and was the first blow in the decline of the Epiphone empire. In his sister Elly’s words, “Epi was the brains.” After his death his two younger brothers Orphie and Frixo took over management. When the war ended in 1945 Epiphone renewed its battle with Gibson, but Gibson never resumed making upright basses, and Epiphone held strong with its bass-making prowess.

The 1946 Epiphone catalog showed this line of basses with a note that many items were not yet back in production; three asterisks meant “prices to be furnished when production is resumed.”

The company emerged from the war with a different face: the man whose name was on every musical instrument had died. Epi passed on June 6, 1943 at the age of 50 from leukemia. This changed the fate of the company and was the first blow in the decline of the Epiphone empire. In his sister Elly’s words, “Epi was the brains.” After his death his two younger brothers Orphie and Frixo took over management. When the war ended in 1945 Epiphone renewed its battle with Gibson, but Gibson never resumed making upright basses, and Epiphone held strong with its bass-making prowess.

The 1946 Epiphone catalog showed this line of basses with a note that many items were not yet back in production; three asterisks meant “prices to be furnished when production is resumed.”

B1

***

B2 ***

B3 $190, west of the Rockies 199

B4 235, blonde or shaded, west 243

B5 325, blonde or shaded, west 333

B2 ***

B3 $190, west of the Rockies 199

B4 235, blonde or shaded, west 243

B5 325, blonde or shaded, west 333

In

early 1949 Frixo resigned from the company and relocated to

Gloucester Ohio, where he intended to manufacture upright basses

under his own label, but failed mainly because he could not

purchase the large widths of fine spruce veneer heneeded.

Apparently “someone” wanted to make it tough for him to build

basses. Paul Fox told me that Frixo was the real bass luthier at

Epiphone. He died in 1957 at the age of 52. I have found three

examples of Frixo-labeled basses from August 20, 1949 (#2),

November '49 and July '50. I made contact with all three owners

and have detailed pictures of their basses. They appear to be

clones of the Epiphone B4 blonde with slightly different details.

Two of these currently reside in Ohio.

Paul Fox has provided a Christmas card from December 1949 that shows Frixo’s daughter Barbara holding a Frixo bass that appears to be a different from two of the three Frixo-labeled basses. So there are probably a few more, a unique part of the Epiphone family legend, and I would like to know more about them.

After Frixo left the company in 1949 Orphie sought help from the CG Conn Company, based in Elkhart, Indiana. The Conn relationship went back to the 1920s, when Continental distributed Epiphone Recording banjos. Orphie granted distribution rights in some territories to Conn and some degree of control. He retained ownership of Epiphone, but the details of the financial arrangement were never disclosed.

Mounting pressure to unionize prompted Conn to move part of the the Epiphone operation from Manhattan to Philadelphia around April 1952. Many of Epiphone's craftsmen of Italian origin refused to move from New York, and they remained to become the backbone of the newly formed Guild Company on October 24, 1952.

The few skilled workers in the Philadelphia plant referred to the less skilled workers as butchers. With neither enough skilled craftsmen nor a dynamic personality in the leadership position, Epiphone was fast becoming a ghost company.

By the mid-'50s Epiphone guitars had deteriorated and proved no competition for Gibson. The only area in which Epiphone remained competitive was its basses, where Gibson had no market presence, while Epiphone basses were still among the most highly respected made in America.

The 1954 Epiphone catalog showed this lineup:

Paul Fox has provided a Christmas card from December 1949 that shows Frixo’s daughter Barbara holding a Frixo bass that appears to be a different from two of the three Frixo-labeled basses. So there are probably a few more, a unique part of the Epiphone family legend, and I would like to know more about them.

After Frixo left the company in 1949 Orphie sought help from the CG Conn Company, based in Elkhart, Indiana. The Conn relationship went back to the 1920s, when Continental distributed Epiphone Recording banjos. Orphie granted distribution rights in some territories to Conn and some degree of control. He retained ownership of Epiphone, but the details of the financial arrangement were never disclosed.

Mounting pressure to unionize prompted Conn to move part of the the Epiphone operation from Manhattan to Philadelphia around April 1952. Many of Epiphone's craftsmen of Italian origin refused to move from New York, and they remained to become the backbone of the newly formed Guild Company on October 24, 1952.

The few skilled workers in the Philadelphia plant referred to the less skilled workers as butchers. With neither enough skilled craftsmen nor a dynamic personality in the leadership position, Epiphone was fast becoming a ghost company.

By the mid-'50s Epiphone guitars had deteriorated and proved no competition for Gibson. The only area in which Epiphone remained competitive was its basses, where Gibson had no market presence, while Epiphone basses were still among the most highly respected made in America.

The 1954 Epiphone catalog showed this lineup:

B4 $340/310

B5 395/375

In

1957 Orphie contacted Gibson stating he had to sell out because

all he had left was his bass business. While the negotiations were

secret, the communication records show that by April 18, 1957 the

deal was done.

Ward Arbanas would head up the new Epiphone division at Gibson. He was sent to New York to pack up the remaining basses, and John Huis was in Philadelphia to inspect the production molds. The deal was to include 35 instruments, 17 of which were finished and shipped to Kalamazoo. There were another 15 in New York that were mostly unfinished parts. The remaining three were recalled from an Epiphone dealer in Denver.

Orphie asked $20,000 for everything. Gibson paid the asking price, and on May 10, 1957 this oddly worded announcement was made: “Epiphone, Inc. of Kalamazoo, Michigan announces the acquisition of the business of Epiphone, Inc. of New York.” This marked the end of an 80-year era; the Stathopoulo family was out of the music business.

I'd heard that disgruntled Epiphone employees destroyed the Epiphone bass molds, but Walter Carterwrites that in March 1958, nearly a year after the operation moved to Kalamazoo, the Conn woodwind factory in New Berlin NY gave employees what they wanted from te remaining Epiphone guitar parts, then torched the rest in a bonfire behind the factory. This event may have sparked that myth.

Curiously, in August 2008 an Ebay auction advertised the original bass molds from the Gibson Kalamazoo warehouse. If the molds were authentic, they would have been the early Gibson cello molds from the 1930s and most likely a later version of the Gibson-Epiphone Kalamazoo molds. The new owner of the molds told me in email, “and now I am going to be the proud owner of THE ORIGINAL mold, templates, arching forms for tops and backs, and inside mold for the original Epiphone bass! The seller got them out of the Gibson building about 15 years ago when he stumbled upon a hidden loft/storage area/crawl space above the men's room.” I presume these molds are the originals, as the history all fits together. The very same molds were parceled out and resold, again on Ebay, in March 2010.

Upright basses were the reason Gibson bought Epiphone, but manufacturing them turned out to be no easy task. In May 1957 Gibson announced a plan to have basses available in the "very near future." There was no room at the Gibson plant in Kalamazoo so Gibson rented a building less than twelve blocks away. Bass production was supposed to be easy with no new models to develop, but the fall of 1957 came and went with no new basses. According to John Huis, “We built very few basses. We just weren’t equipped for them. The Epi equipment, they didn’t have anything in what you would call real good equipment. I think they had gotten rid of it before we got ahold of it.”

Ward Arbanas took charge of the Epiphone division, and he was at first optimistic about bass production, suggesting in a memo dated December 20 1957 that they should add a line of cellos (Gibson’s own prewar cello forms were apparently still intact). But only the following February 13 Arbanas brought bad news from the bass production line. The rented building was not climate-controlled, and abrupt changes in temperature and humidity had caused the finish on the Epi basses to check. John Huis described the real cause: “We rented the space, and then the guy turned off the heat over the weekend.” Every single bass, even the ones Gibson had bought finished, had to be stripped and refinished. When the basses finally hit the market they listed for 25% more then comparable models offered by Kay, $345 for an Epi B4 versus $275 for a Kay C-1.

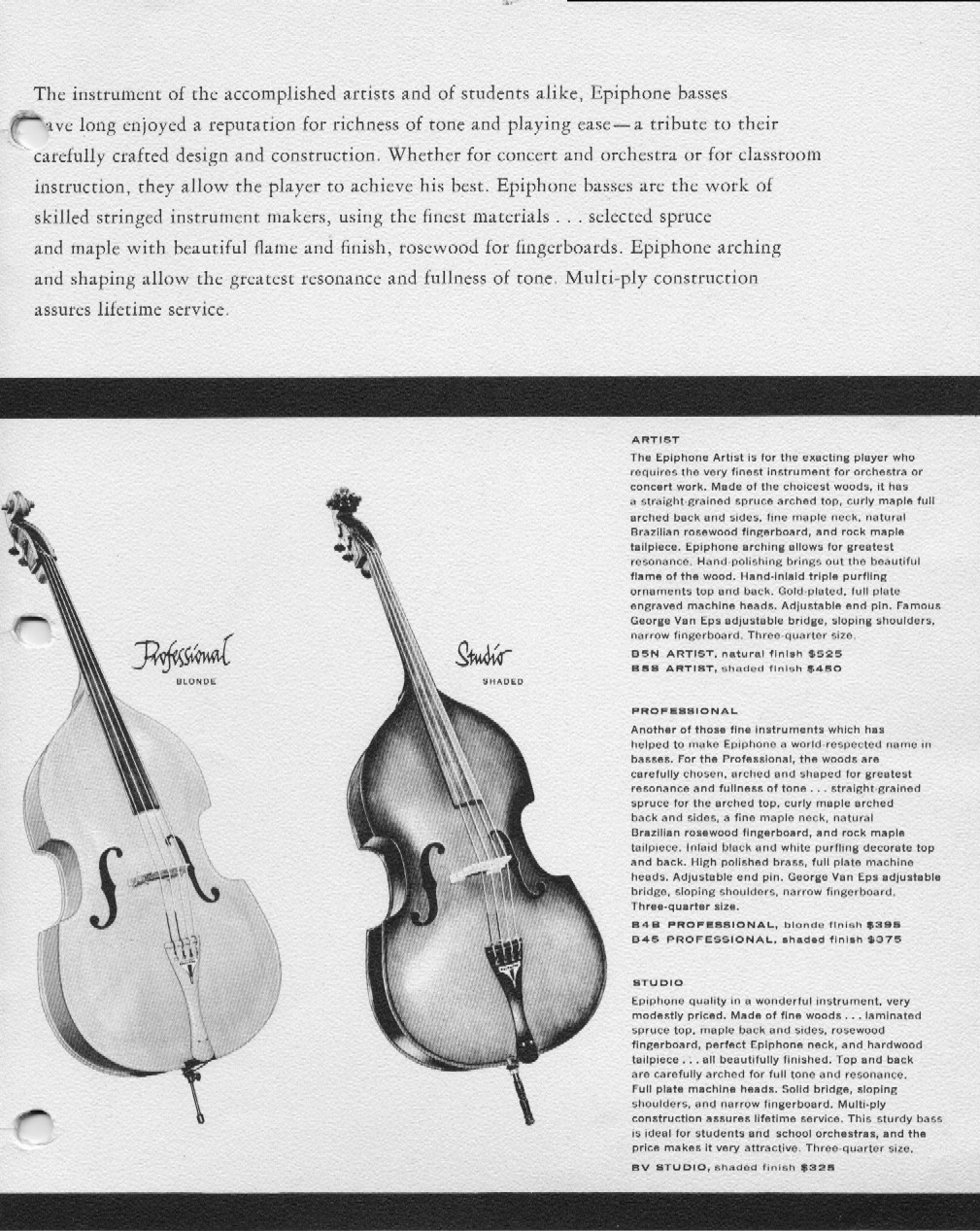

Gibson’s first Epiphone bass flyer from 1958 had this one-page description:

Ward Arbanas would head up the new Epiphone division at Gibson. He was sent to New York to pack up the remaining basses, and John Huis was in Philadelphia to inspect the production molds. The deal was to include 35 instruments, 17 of which were finished and shipped to Kalamazoo. There were another 15 in New York that were mostly unfinished parts. The remaining three were recalled from an Epiphone dealer in Denver.

Orphie asked $20,000 for everything. Gibson paid the asking price, and on May 10, 1957 this oddly worded announcement was made: “Epiphone, Inc. of Kalamazoo, Michigan announces the acquisition of the business of Epiphone, Inc. of New York.” This marked the end of an 80-year era; the Stathopoulo family was out of the music business.

I'd heard that disgruntled Epiphone employees destroyed the Epiphone bass molds, but Walter Carterwrites that in March 1958, nearly a year after the operation moved to Kalamazoo, the Conn woodwind factory in New Berlin NY gave employees what they wanted from te remaining Epiphone guitar parts, then torched the rest in a bonfire behind the factory. This event may have sparked that myth.

Curiously, in August 2008 an Ebay auction advertised the original bass molds from the Gibson Kalamazoo warehouse. If the molds were authentic, they would have been the early Gibson cello molds from the 1930s and most likely a later version of the Gibson-Epiphone Kalamazoo molds. The new owner of the molds told me in email, “and now I am going to be the proud owner of THE ORIGINAL mold, templates, arching forms for tops and backs, and inside mold for the original Epiphone bass! The seller got them out of the Gibson building about 15 years ago when he stumbled upon a hidden loft/storage area/crawl space above the men's room.” I presume these molds are the originals, as the history all fits together. The very same molds were parceled out and resold, again on Ebay, in March 2010.

Upright basses were the reason Gibson bought Epiphone, but manufacturing them turned out to be no easy task. In May 1957 Gibson announced a plan to have basses available in the "very near future." There was no room at the Gibson plant in Kalamazoo so Gibson rented a building less than twelve blocks away. Bass production was supposed to be easy with no new models to develop, but the fall of 1957 came and went with no new basses. According to John Huis, “We built very few basses. We just weren’t equipped for them. The Epi equipment, they didn’t have anything in what you would call real good equipment. I think they had gotten rid of it before we got ahold of it.”

Ward Arbanas took charge of the Epiphone division, and he was at first optimistic about bass production, suggesting in a memo dated December 20 1957 that they should add a line of cellos (Gibson’s own prewar cello forms were apparently still intact). But only the following February 13 Arbanas brought bad news from the bass production line. The rented building was not climate-controlled, and abrupt changes in temperature and humidity had caused the finish on the Epi basses to check. John Huis described the real cause: “We rented the space, and then the guy turned off the heat over the weekend.” Every single bass, even the ones Gibson had bought finished, had to be stripped and refinished. When the basses finally hit the market they listed for 25% more then comparable models offered by Kay, $345 for an Epi B4 versus $275 for a Kay C-1.

Gibson’s first Epiphone bass flyer from 1958 had this one-page description:

Epiphone

Bass Viols … world’s most honored name in basses

B5 Natural $475

B5 Shaded $400

Model B5 … the Artist

A superb instrument for the exacting artist who requires the very finest. Of the most choice woods … straight-grain spruce arch top, select curly maple full arched back and sides, finest maple neck, natural Brazilian rosewood fingerboard and rock maple tailpiece. Hand polishing brings out the beautiful flame of the wood. Exquisite hand inlaid triple purfling ornaments top and back. Gold plated, full plate engraved machine heads. Adjustable end pin. Famous George Van Eps adjustable bridge, sloping shoulders, narrow fingerboard. In shaded (rich Cremona brown) or natural finish. Three quarter size only.

B5 Natural $475

B5 Shaded $400

Model B5 … the Artist

A superb instrument for the exacting artist who requires the very finest. Of the most choice woods … straight-grain spruce arch top, select curly maple full arched back and sides, finest maple neck, natural Brazilian rosewood fingerboard and rock maple tailpiece. Hand polishing brings out the beautiful flame of the wood. Exquisite hand inlaid triple purfling ornaments top and back. Gold plated, full plate engraved machine heads. Adjustable end pin. Famous George Van Eps adjustable bridge, sloping shoulders, narrow fingerboard. In shaded (rich Cremona brown) or natural finish. Three quarter size only.

The

NAMM show in July 1958, held at the Palmer House hotel in Chicago,

would be the resurrection of the Epiphone brand. The splash

created by the new Epiphone guitars seems to have obscured the

division’s reason for being, its upright basses. The new line

included three basses: the B5 Artist, B4 Professional, and new BV

Studio.

By

1961, with Epiphone guitar sales growing steadily, Gibson

abandoned upright basses altogether. The last cataloged

upright basses were shown in 1963.

The

1961 Epiphone catalog showed this lineup:

B5N

$495/425

B4B $375/345

BV $299.50

B4B $375/345

BV $299.50

With

Epiphone guitar sales growing steadily, the last cataloged basses

were shown in 1963. The Epiphone upright bass had come to the end

of the line, and no basses were produced or advertised by

Gibson-Epiphone after 1964.

Epiphone

Models

The

following descriptions of Epiphone bass models are my personal

observations, and not part of or listed in any of Epiphone or

Gibson-Epiphone brochure.

All Epiphone and Gibson-Epiphone basses are the same gamba shape. To my knowledge Epiphone never made a violin-shaped bass. All five models were officially introduced in January 1941, with production startup in 1940.

All Epiphone and Gibson-Epiphone basses are the same gamba shape. To my knowledge Epiphone never made a violin-shaped bass. All five models were officially introduced in January 1941, with production startup in 1940.

B1

The catalog describes this as the entry-level

bass. All examples seen so far are dark brown in color, have a

single black edge pinstripe and no outer rib lining. The top

appears to be laminated maple (not spruce), and ribs and backs are

plain maple with little or no flame. Many of these very early

examples have lost their tail badges and can't be easily

identified. Of those with intact tail badges, some have been

stamped B1 and others have no stamp at all. All the B1s have

serial numbers stamped under the scroll on the bass side. The

earliest B1 seen so far is #257, the latest #696. It appears that

production of this model ended with the onset of WWII (beginning

of '42) and did not resume.

B2

All examples of the next model up are

dark brown with a lighter X contrast pattern and fine double black

edge pinstripes, very similar to the Kay basses, and with outer

rib linings. The top appears to be fine-grained laminated spruce

with lightly flamed maple ribs and backs. Serial numbers are

die-stamped under the scroll on the bass side. Like the B1, this

model did not reappear when production resumed in 1946.

B3

Two examples I've seen of the next model above the

B2 have different finish treatments: one is blonde with a milky

overspray (#267), and the other (#325) has an orange/brown finish

with no contrast pattern. rather than edge pinstripes, B3s have

inlaid edge purfling front and back. A distinguishing

characteristic of the B3 is that the back purfling goes up into

the heel button, with no loop, the only Epi model with this subtle

detail. This model has outer rib linings. The top appears to be

fine-grained laminated spruce with lightly flamed maple ribs and

back. B3 serial numbers are die-stamped under the scroll on the

bass side.

B4

The blonde B4 is the most common model in the

database, with the earliest numbered 159 and the latest 3187. The

B4s have inlaid edge purfling front and back, with a back loop up

to about #1100, and outer rib linings. Tops are fine-grained

laminated spruce with a both highly and lightly flamed maple ribs

and backs. Earlier examples seem to have a higher degree of flame.

Early B4 serial numbers are die-stamped under the scroll on the

bass side up to about #1710. Later numbers are stamped at the end

of the fingerboard. This model was in production till Gibson quit

making upright basses in 1963.

B5 Epiphone’s highest-grade and most ornate bass.

Blonde examples outnumber their shaded siblings. The earliest B5

I've seen is #157, and the latest with its number stamped under

the scroll is #1652.By #1736 serial numbers are die-stamped on the

end of the fingerboard. All B5s have inlaid edge purfling front

and back, black-white-black during the Epiphone years and

white-black-white for the Gibson-Epiphone period. All B5s have a

purfling loop on the back, tuning plates were engraved with a

grapevine motif, and outer rib linings. This was Epiphone’s top of

the line, with fine-grained laminated spruce tops and highly

flamed maple ribs and backs. Tailpieces are usually highly flamed

maple, stained to match the bass. This model also ran till Gibson

ceased production in 1963.

Epiphone

Characteristics

Scroll

Epiphone scrolls are big, beautiful and factory

hand-carved, standing out from those of other contemporary US-made

plywood basses, massive and very distinctive. Early examples are

wider and the volutes bolder and more pronounced than later ones.

Tuners

All Epiphone basses seen so far carry Kluson

tuners, with the company name stamped on the plates of early

examples with five fine incised lines as decoration. Later plates

are plain, finished in bright brass, bright nickel and black. B5

tuners are engraved with a grapevine motif and the words 'Epiphone

B5,' and engraving specifying New York or Kalamazoo according to

its origin.

(Before 2014) I was contacted by Ray of Ray Noguera Musical Engraving. Ray took over the workshop and all the engraving templates after Jerry Brownstein passed away. Jerry was a master engraver, friend and teacher to Ray. Jerry’s engraving work spanned over 60 years, and he was the master engraver for the Epiphone tuner plates used on the high-end B5s. Jerry engraved hundreds of sets of these machines. Ray found the prints for this job in one of the many cigar boxes full of patterns and prints in Jerry's shop.

Jerry’s long list of customers included, Selmer Martin, Conn, Powell, Haynes and Buffet. He also engraved for Tiffany, Cartier, Michael C Fina, James Robinson, and London jewelers Harry Winston. He has engraved millions of dollars of jewelry and silverware, and even the Americas Cup, Stanley Cup, US Open trophies, Winston Cup and many more.

(Before 2014) I was contacted by Ray of Ray Noguera Musical Engraving. Ray took over the workshop and all the engraving templates after Jerry Brownstein passed away. Jerry was a master engraver, friend and teacher to Ray. Jerry’s engraving work spanned over 60 years, and he was the master engraver for the Epiphone tuner plates used on the high-end B5s. Jerry engraved hundreds of sets of these machines. Ray found the prints for this job in one of the many cigar boxes full of patterns and prints in Jerry's shop.

Jerry’s long list of customers included, Selmer Martin, Conn, Powell, Haynes and Buffet. He also engraved for Tiffany, Cartier, Michael C Fina, James Robinson, and London jewelers Harry Winston. He has engraved millions of dollars of jewelry and silverware, and even the Americas Cup, Stanley Cup, US Open trophies, Winston Cup and many more.

Nut

The most common nut seems to be of rosewood with a

step-up design, meaning it does not taper across the fingerboard

at a smooth angle, but has a 90-degree angle from the string edge

down toward the fingerboard.

Neck

Most all Epiphone bass necks are assembled from

two pieces, allowing for the wider scroll and meatier neck than is

typical on Kay basses. There are exceptions: #1430's neck is a

single piece of highly flamed maple; #165 has a three-piece neck

with a 1/8” ebony stringer through the box and scroll; #833 has a

five-piece neck of light-dark-light-dark-light highly flamed maple

through the box and scroll, the only example I've seen of this

ambitious effort by Epiphone.

Fingerboard

So far all Epiphone basses appear to have rosewood

fingerboards. I was under the impression that B5s were supposed to

have ebony boards, but this has not proved out. The grade and

color of the rosewood seems to vary over time, with lighter color

and more narrow fingerboards in later years.

F-holes

There is not a lot to be said about the Epiphone

f-holes other than they are large and very stylistic. Once you

know how they look, you can't mistake them for any other. The

f-hole shape is more subdued in the earliest examples and more

pronounced and wider in later years. Typically the center notches

are wide and sweeping, not the tiny nicks of the Kays or American

Standards. Study them closely and you'll know them when you see

them.

Bridge

While most vintage upright basses have had their

bridges replaced over the years, I have owned an original 1958

Gibson-Epiphone B5 with the original adjustable George Van Eps

Bridge. Van Eps worked closely with the Epiphone Company and

patented the first adjustable bridge in 1946. He was a master jazz

guitarist and iconoclastic inventor, designing a seven-string

guitar in the late 1930s with an extra bass string. He died in

1998 after a long history of musical contribution.

Soundpost

patch Epiphone models do have a soundpost reinforcement

patch, but on the top plate, where it's difficult to see. Most

likely you'll feel it with your finger through the f-hole on the

treble side. The patches are square to rectangular in shape and

range between 3x4 and 4x4” and 1/16”-1/8” thick. Some very early

examples do not have the patch.

Tops

Very early Epis seem to have three-ply tops, with

a reputation for being a bit “mushy” but quick to respond while

being acoustically loud. By late 1950 tops are thicker and

sturdier. I recommend using lighter-tension or gut strings on

early examples to prevent caving the top of the bass. I have seen

no example of a warped Epiphone neck, but a few sunken tops.

Tailpieces

vary from black-painted or ebonized on

entry-level models to highly flamed rock maple or even birdseye

maple on the B5s. B4 and B5 tailpieces are stained or shaded to

suit the bass, but still transparently enough to showcase the

flame.

Tailpiece

badge The iconic Epiphone tailpiece badge is made of

stamped brass with white enamel inlay. It's often die-stamped with

the model designation, but some examples don't have it. Some of

this might be because the company used the same badge on guitar

headstocks during the '40s, and if a bass lost its tail badge a

replacement could be salvaged from a guitar. This still happens

today on the rare occasion that you can find an Epi badge at an

old music store or on Ebay.

Endpin

sets There were several different types of endpin sets.

The most common is a black-painted knob with an adjustable rod.

There was also a fixed set with pins of two different lengths. The

fixed endpin looks like a turned table leg with a rubber tip. I've

seen one example on a B5 made from flamed maple stained to match

the tailpiece.

Epiphone

Serial Numbers

Associating

serial numbers with dates of manufacture is by far the most

difficult task in my research. I have collected histories from

original owners and family members who have documented their

purchases. This remains an exercise in educated guessing, and it

will be updated as new data comes in, so please take it with a

grain of salt.

Placement

I have found three main locations for serial

numbers, all apparently using the same number dies, with the font,

character height and positioning of the serial numbers pretty

consistent. There have been a few exceptions: #s 103, 106, 115,

122 and 125 have the numbers stamped vertically along the rib seam

at the endpin; on #s 149, 157 and 159 the numbers are stamped on

the pegbox right below the tuner plate on the bass side. Very late

Gibson-Epiphone examples may have an interior ID label in addition

to stamped serial numbers parallel to the saddle at the end seam.

1.

Early examples have serial numbers dieistamped on the bass side

under the pegbox. Most often you'll feel them stamped into the

wood before you see them. Occasionally I've found the

numbers stamped on the treble side instead.

2. The next location for serial numbers is on the end of the fingerboard. Again, you'll likely feel it before you see it. If the fingerboard is replaced, the serial number is forever lost. To my knowledge Epiphone did not write serial numbers inside their basses as seen on Kay, American Standard and King basses.

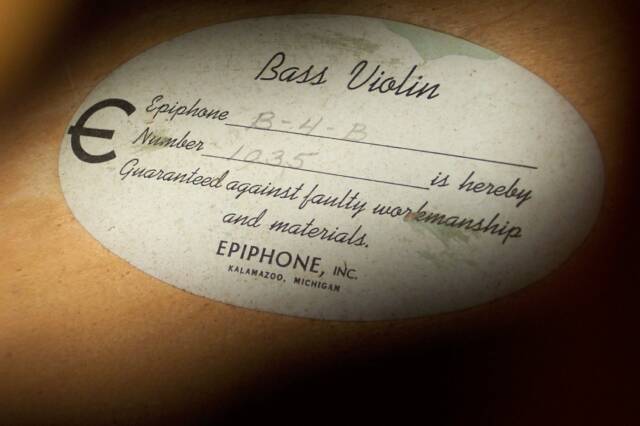

3. The final location for the serial number is the bottom of the bass, parallel with the saddle. This location seems to indicate the bass was made by Gibson-Epiphone in Kalamazoo, and the numbers reset from 100. A few examples have an oval paper ID label or robin's-egg blue tape label from Kalamazoo inside.

2. The next location for serial numbers is on the end of the fingerboard. Again, you'll likely feel it before you see it. If the fingerboard is replaced, the serial number is forever lost. To my knowledge Epiphone did not write serial numbers inside their basses as seen on Kay, American Standard and King basses.

3. The final location for the serial number is the bottom of the bass, parallel with the saddle. This location seems to indicate the bass was made by Gibson-Epiphone in Kalamazoo, and the numbers reset from 100. A few examples have an oval paper ID label or robin's-egg blue tape label from Kalamazoo inside.

Manufacture

dates I have

a firsthand, one-owner Epi bass history for #493 stating the

instrument was purchased in the spring of 1941 in Cincinnati Ohio

while the young man was looking for a college. This tells me that

#100- 500 were most likely built in 1940-41. B2 #715 pushes prewar

production to about #700, and no B1, B2 or B3 has appeared later

than that.

Currently with over 7% of the serial-number range documented on two established date lines, I feel it's well established that bass production began sometime in late 1939, halted during the war (1942-1945), and resumed sometime in 1945. Gibson production began in July 1958. Gibson-Epiphone manufactured about 935 basses (#1035 is the highest Gibson-Epiphone recorded in my database) between '58 and '64. There is no way to know how many of Gibson's 935 were pre-manufactured by Epiphone basses or built from leftover parts.

I estimate that Epiphone built roughly 3,087 basses from mid-1940 to early '57. Gibson-Epiphone built another 935, making roughly 4,022 in total over 23 years.

Currently with over 7% of the serial-number range documented on two established date lines, I feel it's well established that bass production began sometime in late 1939, halted during the war (1942-1945), and resumed sometime in 1945. Gibson production began in July 1958. Gibson-Epiphone manufactured about 935 basses (#1035 is the highest Gibson-Epiphone recorded in my database) between '58 and '64. There is no way to know how many of Gibson's 935 were pre-manufactured by Epiphone basses or built from leftover parts.

I estimate that Epiphone built roughly 3,087 basses from mid-1940 to early '57. Gibson-Epiphone built another 935, making roughly 4,022 in total over 23 years.

Serial

numbers stamped under the scroll indicate New York production.

Those on the end of the fingerboard indicate Philadelphia

production starting in April 1952. Those on end block parallel

with the saddle indicate Gibson-Epiphone production in Kalamazoo.

*Epiphone

Production Serial Numbers:

#103,

late 1939: prototype, no tail badge, decal at button

#106, late 1939: prototype, with tail badge stamped "4" and decal at button

#115, late 1939: B3 prototype, no tail badge

#122, early 1940: B2 prototype, no tail badge

#125, early 1940: B3 prototype, no tail badge

#149, mid-1940 B3: serial number on side of pegbox, with tail badge

#165, mid-1940 B4: beginning of standardized production, with tail badge

#165-715, mid-'40-late '41: made in Manhattan

#106, late 1939: prototype, with tail badge stamped "4" and decal at button

#115, late 1939: B3 prototype, no tail badge

#122, early 1940: B2 prototype, no tail badge

#125, early 1940: B3 prototype, no tail badge

#149, mid-1940 B3: serial number on side of pegbox, with tail badge

#165, mid-1940 B4: beginning of standardized production, with tail badge

#165-715, mid-'40-late '41: made in Manhattan

Early

1942 through 1945 production may have been halted for WW2

#716-1682,

early '46-late '51: made in Manhattan

Following

apparent Epiphone strike in early 1952

#1706-3187,

late '52-late '56: made in Philadelphia

Gibson-Epiphone

Production

#152-1035,

July '58 thru '64: made in Kalamazoo

Epiphone Upright Bass

Research Project

Research Project

Updated

January 2014

Special

thanks to Paul Fox, Phil Flanigan, Donnie Crist, Debra

Hiptinstall, and others for their contributions of historical

photos and information.

This

is a large 5MB file with many vintage photos. Please be patient

while it loads. It is worth the wait.